by Lindsay Holmes – Huffington Post

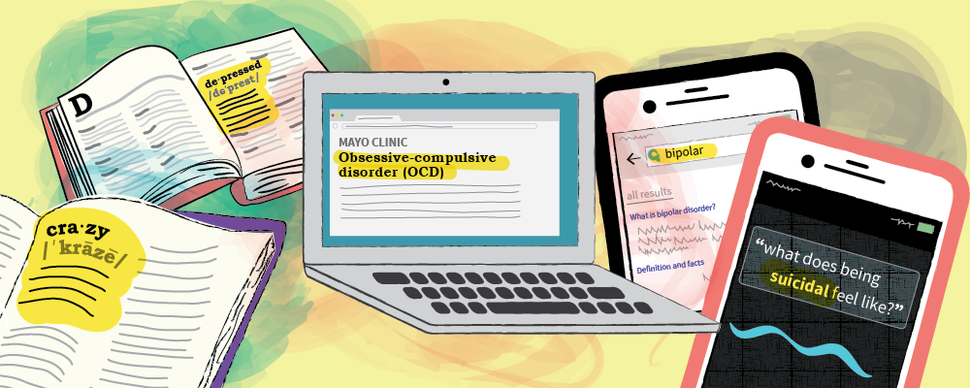

Our cultural lexicon can trend toward the dramatic. A really good TV show is going off the air? We’re “depressed.” A political candidate proposes a policy we disagree with? They’re “crazy.” We want to change our outfit for the third time in a day? We’re “bipolar.”

But we shouldn’t use mental health-related phrases in ways that aren’t literal.

Using mental health terminology in a pejorative or trivializing manner can be damaging. As Dan Reidenberg, the executive director of the suicide awareness organization SAVE points out, it largely contributes to the stigma surrounding mental health disorders.

“It’s actually demeaning to those with true illnesses that can’t easily stop these behaviors,” he told The Huffington Post. “If we trivialize them into something else or we make that become the person’s identity, we have done everyone a disservice.”

Simply put, medical conditions, including mental health disorders, don’t make for good metaphors.

Seemingly small issues like word choice have a much broader context: Mental illness has often been viewed as a personal flaw that needs to be fixed rather than a condition that requires treatment. People still blame mental illness for violent crimes. It’s why people dealing with a disorder stay silent. And it’s why people throw around phrases like “mental case” as an insult or for dramatic effect.

The only way to fix the culture is to address stigma directly, Reidenberg said. That starts with the words we speak.

Below are just a few examples of mental health terms that have seeped into our everyday language ― and what experts say we can do about it:

Bipolar

On its own, bipolar disorder is a mental health condition characterized by manic and depressive episodes, which are clinical mood disturbances. But in society, the term is used as a way to describe someone frequently changing their mind.

Bipolar disorder affects 2.6 percent of adults in the U.S. And as anyone who experiences the condition will attest, it’s not something that just causes a change of heart or indecision. It can lead to a dramatic loss in sleep, productivity and motivation.

This is where education comes into play, Reidenberg says. The more we understand what a disorder entails, the more it can become normalized in society. That means looking at it just as we would look at a physical health issue.

“We don’t stigmatize people with cancer, liver disease, diabetes or heart disease and we shouldn’t for those living with a mental illness ― after all, it is a brain disease,” he explained. “Ultimately, remarks like these hurt and they keep people from seeking help.”

Crazy

“Crazy” is arguably one of the most widely-used terms. While its meaning is mostly innocuous, it does have the potential to stem into something more stigmatizing ― particularly when it’s used as an insult.

“Words like ‘crazy’ or ‘committed’ are just less than sensitive,” said Christine Moutier, the chief medical officer at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “But it’s a challenge because some of these phrases are so embedded in our everyday vocabulary that they’re almost invisible to us unless someone points it out.”

However, Moutier believes that it won’t always be so deeply ingrained in our colloquial diction. While mental illness was regarded as an oddity or even a crime by earlier generations, waves of young adults are starting to flip the narrative on mental health.

“There are very significant advances going on with younger generations when it comes to destigmatization,” she said. “We’re noticing that more young people are quite open about their mental health issues … and I hope that creates a trend of people responding in a very supportive way rather than coming from a place of ignorance.”

Depressed

There’s a common myth that depression simply refers to exhibiting sadness. But, as Moutier points out, there’s so much more to the health condition ― and it can be demoralizing to those who have it when someone uses the term “depressed” as slang.

“Depression is a more profound experience than just feeling sad or frustrated,” Moutier said, adding that the disorder also brings about sleep troubles and other physical symptoms like headaches and changes in appetite. “The problem with using that language is that it keeps perpetuating the idea that mental health conditions are just momentary experiences from the neck up.”

Depression affects 350 million people globally and is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide. It’s one of the most common mental health disorders, yet many people still don’t believe it could be something that affects them or their family, Moutier says. That’s why using the term as a way to dramatically paint a portrait of feeling sad may go unnoticed.

“There’s a need for deeper understanding, empathy and advocacy,” she said. “These phrases are alienating for sure and only point out how most people don’t understand the fullness of the disorder.”

OCD

Obsessive compulsive disorder affects approximately 2.2 million people. It’s a disorder that brings about intrusive thoughts and extreme anxiety.

But in slang terminology, OCD is often incorrectly conflated with good organization or cleanliness. “Joking about having OCD when a person is just meticulous about something makes it seem like you don’t have a full understanding of the disorder,” Moutier said.

As writer Julie Zack Yaste explained in a HuffPost blog, people also tend to view these mistaken “characteristics” of OCD as something that’s en vogue rather than seeing the disorder for what it really is:

OCD doesn’t mean being fastidious. It doesn’t mean being a perfectionist. It doesn’t mean keeping a clean house. It means living a life feeling apart, abnormal even. I cringe a little when I hear someone say: “I’m so OCD!” simply because they keep a spotless kitchen. That’s not OCD. There’s an almost positive connotation to OCD because it is associated with being driven and hygienic.

It’s crucial to stop watering down these terms, Reidenberg says. And, most importantly, to stop treat mental illnesses as labels. A person is not “so OCD” for making sure they locked the door or for organizing their shoe closet.

“You might have OCD, but you are not OCD,” he stressed.

Suicidal

This is perhaps the most offensive of any mental health term used as slang, Reidenberg says.

“We must help people understand that any time someone says something about suicide, the world stops and we have to focus on that person. Right there. Right now,” he said. “If we hear this and they say that’s not really what they meant, we need to tell them not to say it anymore because suicide is serious so we’re going to take all statements about it seriously. This is really important people who casually make the ‘I’m just going to kill myself’ comments.”

But it’s not just direct comments that have this kind of negative effect. Moutier says subtle cliches also have unintended references toward suicide. “Even colloquial phrases like ‘just shoot me now,’” can be stigmatizing, she explained.

Ultimately, both experts agree that there’s a pretty distinguishable line between someone using slang and someone who is actually expressing signs that they intend to carry out an act of self-harm. But every word holds meaning and it’s crucial to understand the gravity of mental health issues and express compassion toward that community, regardless if it’s a joke or something more serious.

“We should avoid judgment words whenever we can,” Moutier stressed. “It’s difficult when they’re essentially invisible to us, they’re on TVs and in movies. But what someone jokes about could have been a jarring experience for someone else. It’s important to remember that.”

Read the original article in full on Huffington Post.